Scanners are starting to become less prevalent now that digital cameras are all the rage. Essentially a scanner will take some form of printed media and generate a bitmap image from it. A common use for scanners is to digitise photos (done with old 35mm cameras) or to perform OCR (see next section). The photo is placed face down on the glass and a special sensor will travel the full length of the printed media in order to convert it into a bitmap image.

When an image is digitised it is converted into a series of dots or pixels. The pixels are then stored as binary data. The exact mapping of pixel to binary is beyond the scope of this book and also varies depending on the type of picture it is. For example a JPEG binary format is much different from a TIFF or GIF.

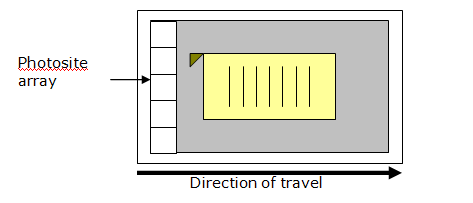

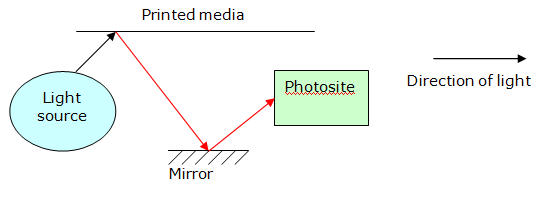

The scanner works by using what is known as photo-sensitive receptors or photosites. When light is incident on these diodes then an electric signal is produced. This signal is slightly different depending on the colour of the light (or the wave length of the light). The scanner will aim a beam of light onto the media to be scanned; the light will be reflected back and then picked up by the array of photosites. The scanner head will pass along the whole of the document slowly.

The above diagram is not accurate but does give an interaction on what actually occurs. A light source will aim a beam of light at the printed media. The light will then be reflected and will be a different colour, based on what part of the document it reflected off. This is shown in the diagram as the beam turning red. A mirror (or collection of mirrors) will then direct the beam into the photosite.